Origins of Pahari

'Sar Zamin-e-Hind par, aqwaam-e-alam ke Firaq.

Kafilay chalte gaye Hindustan banta gaya.'

(On the land of Hind, caravans of many peoples kept arriving and India kept becoming.)

-Firaq Gorakhpuri

Historical Account

Neolithic Iranian farmers (7000 BCE)

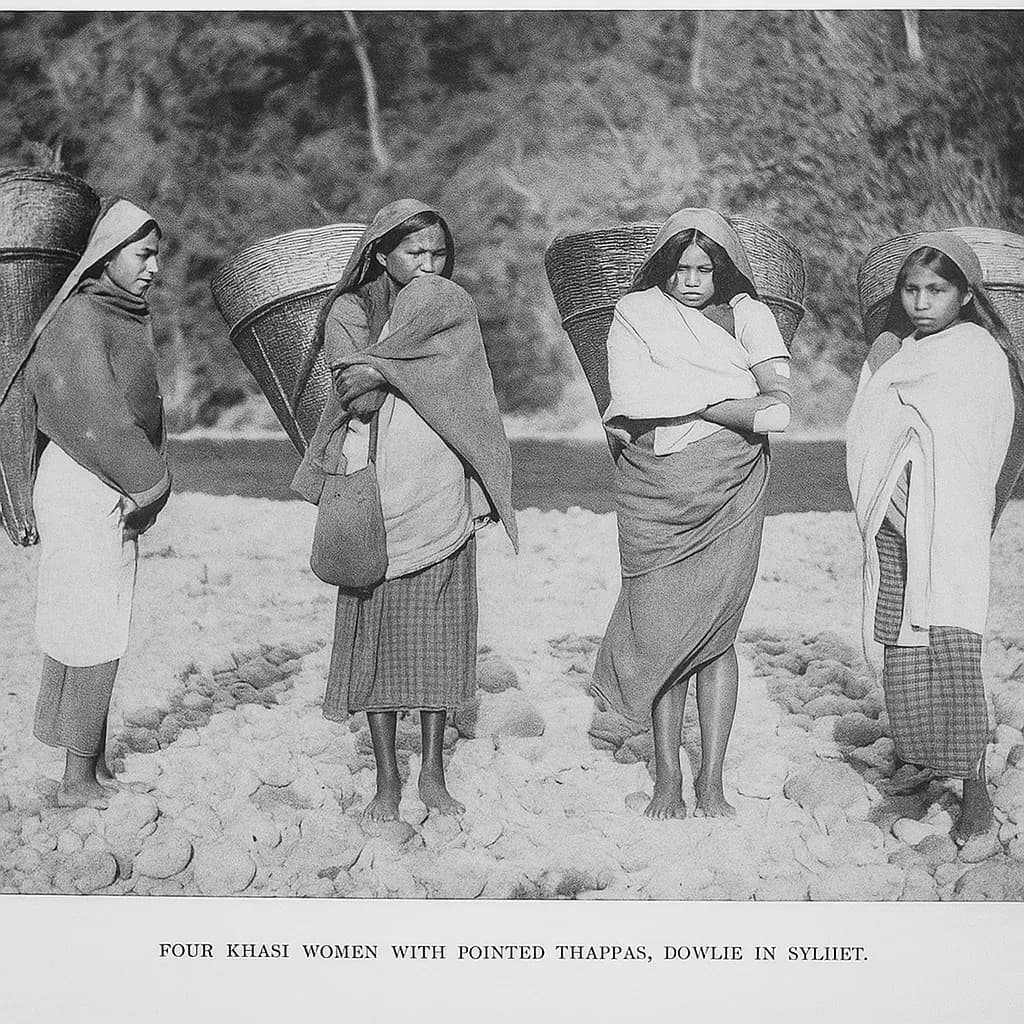

Khasha Tribes

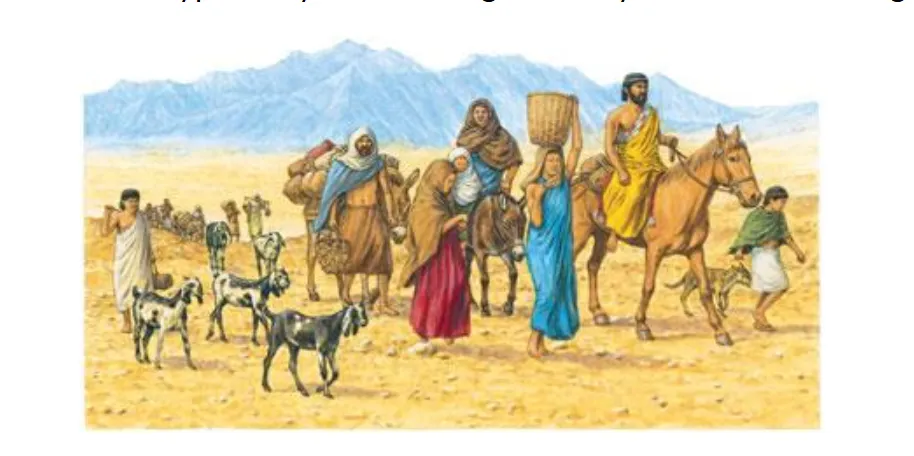

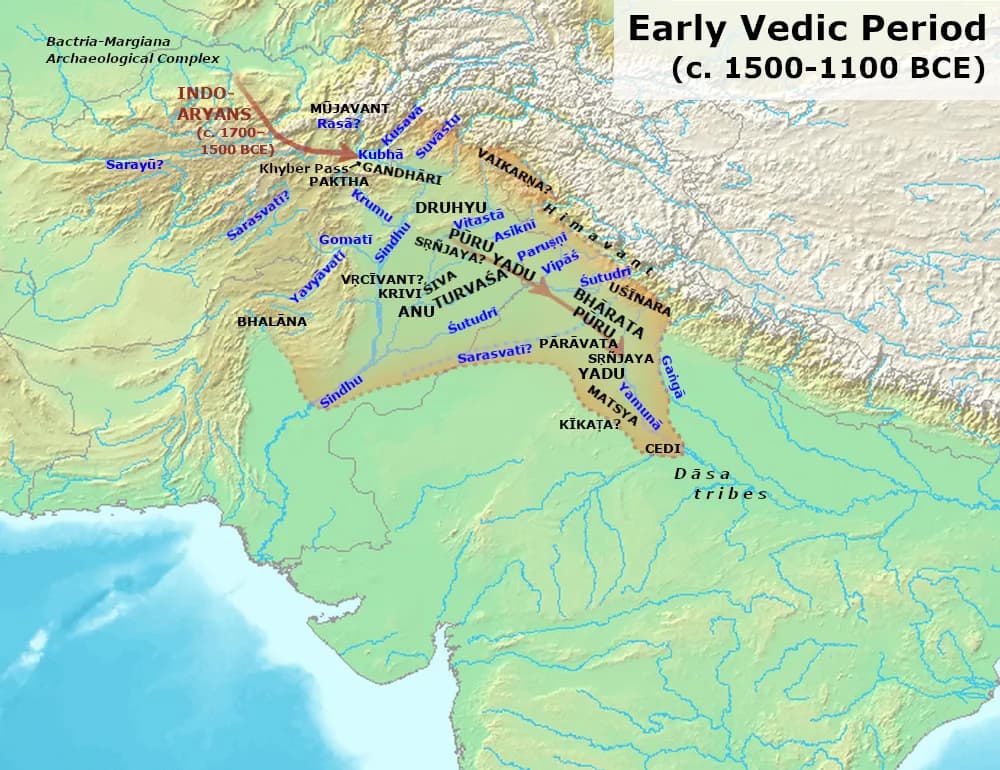

Indo-European steppe migrants (2000–1500 BCE)

Archaeological Footprints

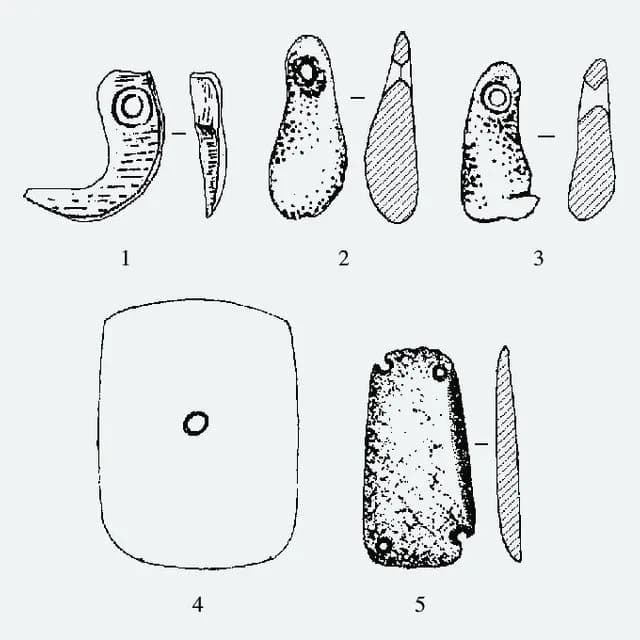

Though historically under represented in mainstream narratives, archaeological sites in Kashmir, like Neolithic pit dwellings at Burzahom and Gufkral reveal transitions from hunter-gatherer to agricultural lifestyles, mirroring Pahari tribal evolution. More than two hundred stone horsemen sculptures linked to the Hephthalites (White Huns) and later Dogra-Pahari warriors were found at these sites. At another archaeological site Bomai Rock Shelter, engravings depicting hunting scenes, possibly reflecting early Pahari subsistence patterns have been seen.

These sites describe on Pahari material culture, settlement patterns, burial sites and petroglyphs to highlight the early life ways of Pahari tribe. Evidences of their rich material history have been found during these archaeological survey, including: settlement patterns, tools, sacred markers, rock art which contribute to a layered understanding of Pahari heritage.

Ancient Civilization Ethos

Shakta Tantra and the Great Goddess in Early Medieval India

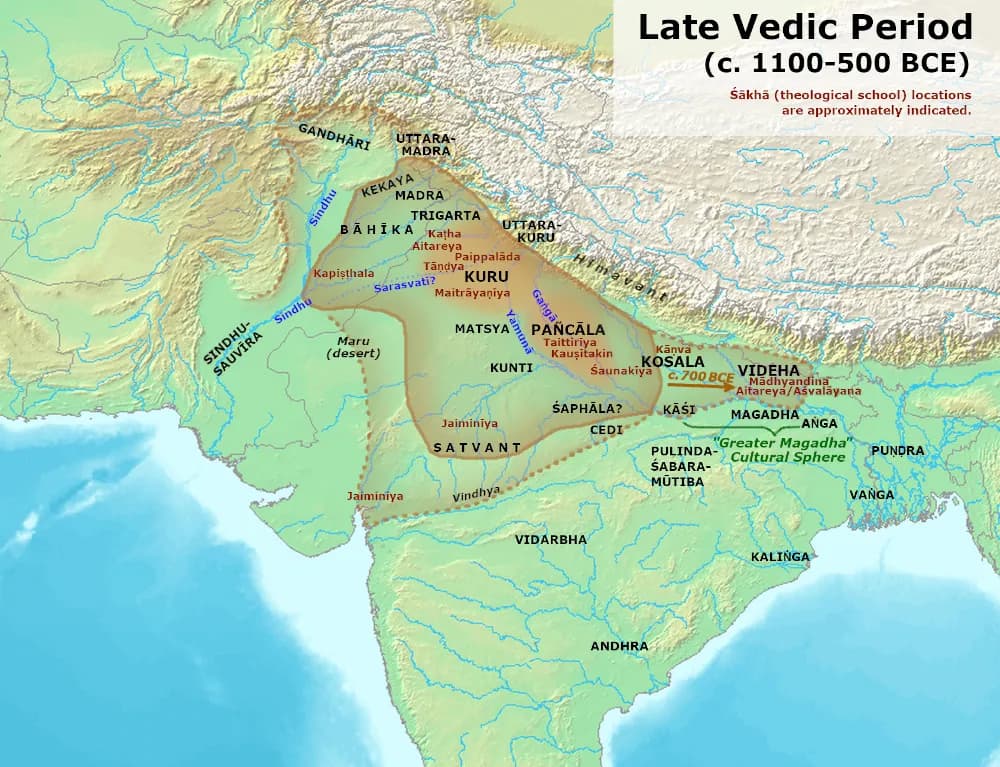

Late Vedic Culture (1100-500 BCE)

Early Vedic Culture (1700-1100 BCE)

'As per Pahari Mythology the first human was born after the gods.

The imaginary world of the Paharia was known as Indakup Bhuinghar- the underworld.

Even the sunlight was inept at reaching there. After God's birth in nether region,

the first human to take birth in that sacred place was a Pahariå'

(Sahitya Akademi; Stories and Myths of the Pahari Community)

पर्वतवासी शूराणां अस्मिन क्षेत्रे समृद्धिम् |

कालपाति गृहमण्या बुद्ध्या धर्मेण च बन्धुतां ||

The people who reside in the mountains are known for their valor and resilience and their lands,

though harsh and remote, remains prosperous due to the wisdom and fair rule of the kings of Kashmir.

Shloka (Rajatarangini) 6.124:

तक्षशिलामणवो नात्यन्तं पर्वतानि यत्र युयुत्सुः |

निपीड्य पर्वतानि संग्रामेण युध्यन्ति च ये तत्र ||

'Even the Takshashila region, with its strategic mountain passes, saw warriors

from the hill tribes engaging in fierce battles, asserting their dominance over the highlands.'

Vedas to Valley: Tribe in Ancient Scriptures

Rajtarangini has numerous references from Mahabharata

Shloka (Rajatarangini 7.29):

दंष्ट्रशोणितमर्दीनां शान्त्या पर्वतगम्भीरम् |

पर्वतवासिनां नृपते: स्थितं धीरमात्मनं ||

Translation

"The mountain dwellers, living in the deep valleys of the Pir Panjal,

who had been restless and rebellious,

were pacified by the wise and just rule of the king,

whose influence reached even the remote peaks.

Shloka (Rajatarangini 5.53):

पर्वतानां समृद्धिं च यत्र तेषां धनं समृद: |

पत्याः समाश्रिता: काश्यं शरणं यान्ति शाकिनः ||

Translation:

The mountains around the Pir Panjal, rich in resources,

were a source of great wealth for the kingdom,

and their inhabitants, while sometimes rebellious,

always came to seek refuge or pay tribute to the ruler of Kashmir.

Shloka (Rajatarangini 6.70):

पर्वतस्य महागर्भे यत्र पश्यन्ति सुरक्षिण: |

राजा कश्मीरेण युक्तो बालधन्यं स्वकं पतिं ||

Translation:

The great depths of the mountains,

where even the gods would be hard-pressed to find a safe place,

became the battlegrounds for the armies of Kashmir,

where the brave kings led their troops against invaders.

NILMATPURANA

nāgāś caiva mahāvīryāḥ pisācāś ca mahābalāḥ

Translation:

"The Nāgas of great valor and the Pisācas of mighty strength were the first inhabitants."

MAHABHARATA

Sanskrit (Bhishma Parva 6.29.33):

गच्छन्ति पर्वतयुतेषु लोकाः सर्वे बलासुराः।

Translation:

"The warriors from the mountain regions, all of them fierce as demons, march forward."

'Jithé paani vándde, uthey dharm vi vándde nahīn.'

Where water is shared, faiths are never divided.

Whispers of Soul and Echoes of Nature

For the ancient Pahari tribes, mountains, rivers, forests and animals were living sacred beings, honoured through rituals, festivals and oral traditions that connected communities to the cosmic order. The Pahari tribes have lived for centuries as custodians of a deep ecological wisdom, one that sees no boundary between humans, animals and the divine. One clear example of nature worship (Animism) among the Pahari tribe is their veneration of the Kishan Ganga River. "Parbat sab da hai, sirf mandir ya masjid da nahin." The mountain belongs to all it is not just the temples or the mosques.

Every element of nature was imbued with spirit, trees were elders, animals were kin and mountains were living deities. For the ancient Pahari tribes of the Pir Panjal earth was revered as Matrikas (divine mother), rivers cherished as bodes of local deities or ancestral spirits and animals regarded as fellow kin's

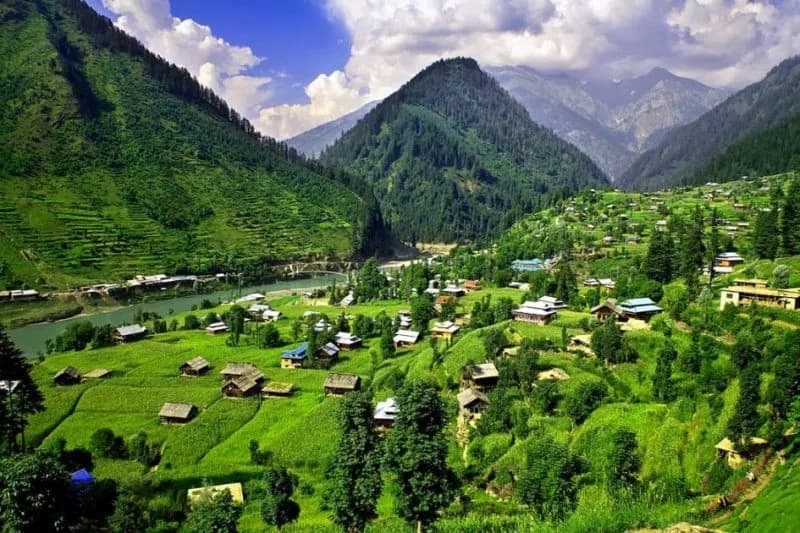

Karnah Valley: A Realm Cradled by Peaks

Perched 6,000 feet above sea level in the northwest of Kashmir, the Karnah Valley lies between the Shamshabari and Karanu ranges, where Gujjars, Bakarwals, Paharis and Sikhs coexist. Accessible only by navigating the treacherous Nastachun Pass (10,000 feet), this land is split by the Kishanganga River at its heart. The Shamshabari range stands at an altitude of 12,000 feet remains snow-covered for most of the year, with glaciers that feed the Batmoji River, a vital water source for the Karnah region.

Karnah was once a Satsar, a primordial lake mirroring Kashmir’s ancient geography. Villages like Tangdhar and Dildar slept beneath its waters, while Zarla, now a wind swept plateau, thrived as a prosperous hilltop heaven. Raja Karan, the valley’s mythic founder, sculpted civilization from wilderness. He split the Aaridal Ridge, unleashing floods that birthed the Kishanganga and etched Karnah’s destiny into stone.

In 1846, Maharaja Ranjit Singh crowned Teethwal as valley’s administrative capital, however, the 1947 tribal invasions severed Karnah’s northern limbs at Shardha, Lipah, Ashkot leaving them marooned across the LoC. Teethwal’s bustling crumbled to ashes and Tangdhar rose as the new tehsil capital.

%20Pass.webp&w=3840&q=75&dpl=dpl_3Yn4eFBYP5J8PMWjeCu7Va2gqMSz)

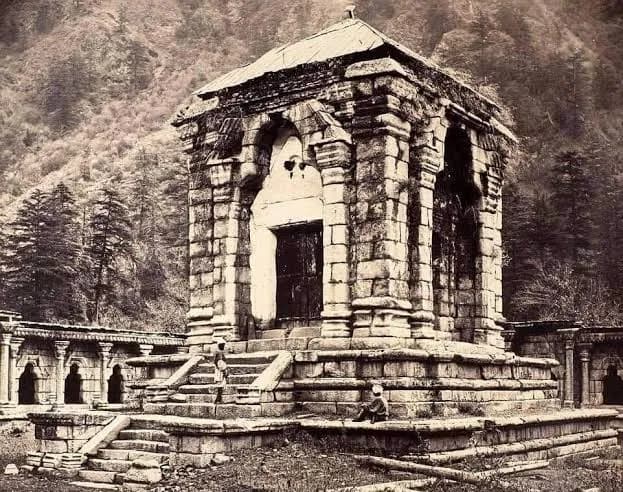

Sharda Peeth: Throne of Goddess Sharda and Fountain of Ancient Knowledge

Sharda Peeth, nestled in the tranquil village of Shardi (Muzaffarabad), stands at the sacred confluence of the Kishanganga, Madhumati and Sargun rivers. Revered as the divine seat of Goddess Saraswati worshipped here as Sharda, the goddess of wisdom it was once among the foremost centre of learning in ancient India. Built in majestic red sandstone and classic Kashmiri style, its towering 20 feet walls and 16 feet pillars were documented in the 19th century by British archaeologist Aurel Stein. It flourished as a university that attracted seekers from Nepal, Tibet, Japan and beyond. The Sharda script born here became a powerful tool for spreading Buddhist philosophy across the Himalayan world.

The roots of Sharda Peeth reach back to pre-Ashokan times, when the Pahari speaking communities linked to great minds like Chanakya and rulers like Chandragupta Maurya emerged as its cultural stewards. Karnah Valley served as a vital gateway between Kashmir and Sharda Peeth. Until 1947 partition, pilgrims and scholars passed through this corridor to worship goddess Sharda. Sharda Peeth is a living symbol of devotion, learning and the spiritual soul of Paharis.

Sharada Mata Temple, Tithwal

Ruined Sharda Fort Pakistan Occupied Jammu & Kashmir

Sharda Peeth Ancient Time

'Ik chulhé di roti, kai dharman di khushboo.'

One hearth’s bread carries the fragrance of many faiths.

Symbolizing shared food, family and diversity in beliefs.

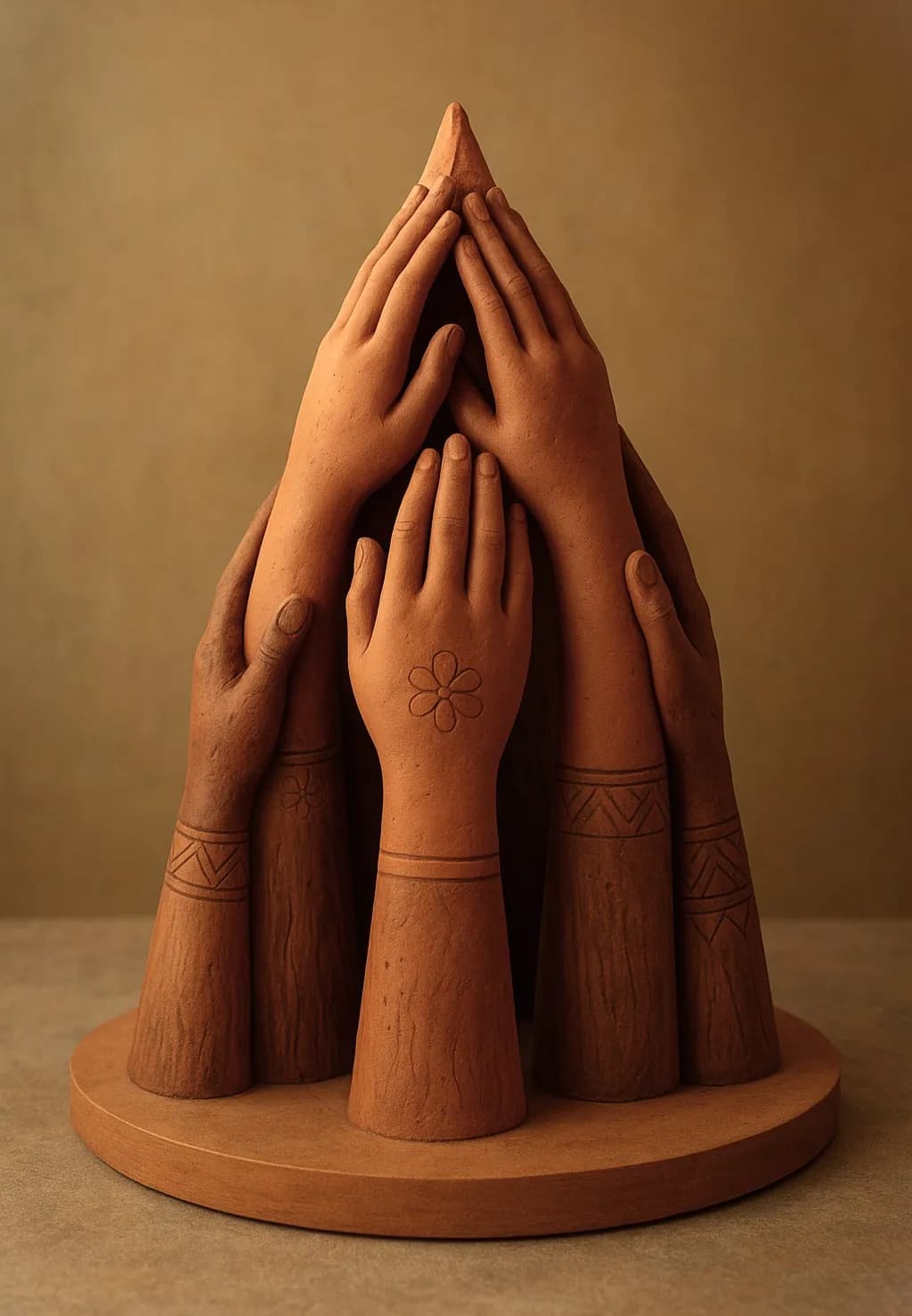

Interfaith Coexistence among the Pahari Tribe of Jammu & Kashmir

Unity in Diversity

'Dua te prarthna, dono pahad ch ghoonjde ne.'

Both dua (Islamic prayer) and prarthna (Hindu prayer) echo in the hills.

This proverb illustrates coexistence of religious practices in shared landscapes.

With the spread of Shaivism and Vaishnavism in the Himalayan region during early medieval times, many Pahari communities began integrating Hindu deities like Shiva and Vishnu into their belief systems, often blending them with their indigenous cosmologies. Hinduism, as a broader sociocultural force, brought temple worship and new ritual practices, but remained syncretic in form. Later, with Sikh incursions and influence during the 18th and 19th centuries, some segments of the Pahari population adopted Sikh tenets, especially in areas of political or economic exchange with Sikh kingdoms.

The Pahari tribe of the Pir Panjal region in Jammu and Kashmir embodies a deeply rooted interfaith ethos, shaped by centuries of coexistence among diverse religious traditions including Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism and indigenous belief systems. Despite religious transitions and external influences, the Paharis have nurtured a culture of brotherhood, mutual respect and harmony, where temples, mosques, gurdwaras and shrines often transcend rigid sectarian and religious boundaries. Shared sacred spaces, joint participation in cultural ceremonies and a common reverence for the natural landscape reflect their inclusive worldview.

'Sajjna na puchhdé zaat te mazhab.'

True friends ask not about caste or religion.

(Popular in Pahari oral culture, this proverb encourages brotherhood above identity.)